[ad_1]

It’s a beautiful, 60-degree day, the sky a cloudless blue. Spunn Road is lined by stately houses looking down on the historic main street of Jackson, California, the high peaks of the Sierra Nevada mountains visible in the distance. There’s a slight bend in the road—and there it is. A chain-link fence topped with barbed wired blocks access to a few dilapidated buildings and a 50-foot-tall rusting steel structure that, in another life, hoisted rock from the depths below. There’s a sign on the fence: TOXIC HAZARD KEEP OUT.

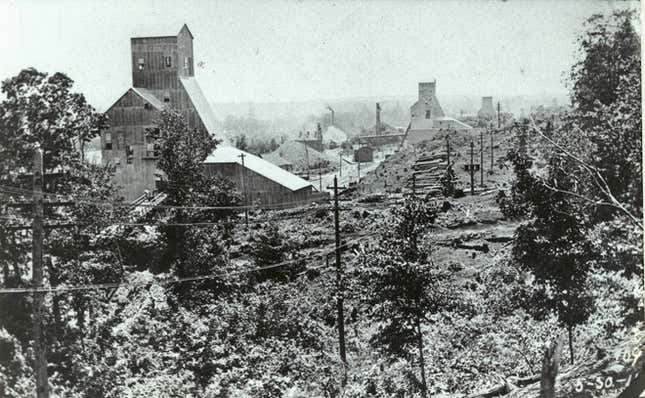

Argonaut Mine is located in the middle of the literal Mother Lode at the heart of California’s Gold Country region. It operated on and off from the 1850s until World War II. After that, the mine sat largely vacant as the town of Jackson grew around it. Today, the only obvious remains are the buildings and, visible across the valley, the remnants of the neighboring Kennedy Mine, which just beat out Argonaut for the title of the deepest mine in the state.

At Kennedy, the miners constructed an elaborate series of multi-story wooden wheels one can still visit today to lift the mine waste, called tailings, and dump it in the valley below. At Argonaut, they dumped the waste—full of arsenic, lead, and other heavy metals brought up from underground, as well as cyanide and mercury the miners added to help extract the gold—a few blocks away.

From the road, all that’s visible of the tailings area today is a large, muddy vacant lot, marked by no more than a small sign on a flimsy-looking fence. One can see where part of the fence was replaced last year after a drunk kid plowed through it.

But the brown muck here is acidic and has average levels of arsenic, an element that can cause cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and skin lesions, of 400 parts per million. The level at which the state requires a site to be cleaned up is 100 parts per million. John Hillenbrand, a geologist with the Environmental Protection Agency, says he once recorded a value of 90,000 parts per million. Mercury and lead levels are also well above acceptable values.

At the bottom of the mining site, there’s also an old, four-story tall concrete dam, built in 1916 to prevent waste from the mine from flowing downstream. In 2015, the US Army Corps of Engineers declared the mine structurally unsound. If it failed, the agency said, it would send a 15-foot-deep mudflow past Jackson Junior High School, built directly below the dam, and into town. Within a year, Argonaut was listed on the National Priorities List, the list of so-called Superfund sites that are among the most contaminated places in the country.

Despite the cleanup at Argonaut being in the early stages, and the site being, as Hillenbrand describes it, “more straightforward” than most Superfund sites, the agency has already spent $8 million over the last several years. He says they have at least $14 million more to go.

And Argonaut is just one of thousands of abandoned mines littered across Gold Country.

Pre-1975, there was no state or federal law mandating cleanup of mining operations, and, in most cases, the miners or companies that operated these sites are long gone. Today, there’s an alphabet soup of state and federal laws and agencies that govern abandoned mines, but coordination is challenging, money is tight, and the projects themselves are complicated.

Though most abandoned mines aren’t toxic, those that are continue to leach out harmful contaminants like lead, mercury, and arsenic. Some are large, complex sites like Argonaut, requiring years of cleanup and millions of dollars. Many are smaller, left in the hands of under-resourced municipal governments or private landowners that are often unaware, unable, or unwilling to address the toxic legacy of mining.

“If you can’t see it, human nature is to minimize it,” says Hillenbrand. In Gold Country, though, where the history of mining is literally imprinted on the landscape, one would think it would be hard to miss. Yet because of money, legal wrangling, and local resistance, California has only just started to truly grapple with the toxic legacy of the Gold Rush and the threat it poses to people today.

Though gold is found throughout California, it’s the western foothills of the Sierra, a large swath in the central-eastern half of the state snaking along the north-south corridor of State Route 49 (named for the 49ers of the Gold Rush) that claims the title of Gold Country. With its rolling, oak-covered hills, expansive open space, and postcard-worthy historic towns, the region has become a popular destination for tourists and outdoor enthusiasts.

Yet, the region remains rooted in its frontier history, with countless reminders of the Gold Rush that gave birth to this quirky corner of the state. Towns have names like Emigrant Gap, Chinese Camp, and Rough-and-Ready, which seceded briefly in 1850 to avoid mining taxes and continues to celebrate ‘Secession Days’ each summer. There’s Sutter Creek, the ‘Jewel of the Mother Lode,’ and Placerville, nicknamed ‘hang town’ for a slew of Gold Rush-era public executions that took place there. In towns-turned-state-parks like Coloma and Columbia, one can give panning a try. Up the road in Nevada City, another 19th century boomtown, the community center is based in the old ironworks foundry, and a water cannon for hydraulic mining is prominently displayed in the town center.

Meandering along Highway 49, aptly called the Golden Chain Highway, one could believe that historic gold mining in the region was a rudimentary undertaking. Andrew Isenberg, a historian at the University of Kansas, describes the prevailing narrative of the period as that of a “windfall adventure.”

“People, they want to actually reenact this collective memory that we all have of mining as this environmentally benign thing that’s all kind of fun,” says Isenberg. But that’s a myth, he explains, pushing back against the very notion of a gold ‘rush.’ “That’s the romantic story,” he says. “In fact, gold mining is about the rise of industry in the United States.”

In reality, the deposits that could be excavated by hand in the Sierra Nevada were played out in a year. Of the tens of thousands of miners that descended on California in 1849, few ever found their fortune. Most went home. Those that stayed, though, developed increasingly invasive—and destructive—means of getting at the gold.

They dammed and diverted waterways to strain whole streambeds. They suctioned up bottom dirt from high alpine lakes and dug shafts deep into mountains of gravel above gold-bearing rivers. At the hydraulic mines, they washed away entire hillslopes with powerful water cannons, capturing nuggets of gold exposed within and leaving a slurry of mud, gravel, and mercury (added to the process to help bind with the gold) behind.

In some places, like Argonaut, miners dug to get at deposits of gold trapped in quartz veins deep underground. Contrary to the notion of a brief ‘rush’ in the 1850s, lode mining, as that method is called, took off in California much later and continued well into the 20th century.

According to Isenberg, people at the time understood the full impact of what they were doing.

“The industry is not really trying to hide this. They’re not saying that what they’re doing isn’t bad for the environment,” explains Isenberg. “They’re just saying, essentially, you got to break some eggs to make an omelet.”

It helped, of course, that, for over a century, no one would be held responsible for the damage.

Without any protections in place to require cleanup of mined lands, the Gold Rush—and the decades of invasive mining that followed—left a legacy of safety hazards and toxic contamination.

Today, the Department of Conservation estimates that there are roughly 47,000 abandoned mines across California, located across public and private land in almost every county in the state.

Experts admit that the 47,000 estimate is just that—an estimate. “For anybody to ever assert that there’s a determined number, a known number of abandoned mine features… it’s absurd,” says Scott Ludwig, the head of the Forest Service abandoned mine lands program. “I mean, every time we go out in the woods, whether it’s a trail crew, timber crew, or whatever, they find stuff.”

Hillenbrand at the EPA adds that the 47,000 number is also not helpful. “I don’t like that number. It’s just so intimidating,” he argues. According to Hillenbrand, the number “narrows down very rapidly” when one only considers sites that threaten public health. The Department of Conservation, for example, estimates that just 5,000 or so mines are contaminated.

“There’s a lot of mines, but we need to focus on sites that are close to people, that pose a real environmental harm,” says Hillenbrand.

But what exactly does it take for a vacant plot of land, or a pile of seemingly innocuous dirt, to pose a threat?

For the thousands of non-contaminated sites, for example, being clean isn’t the same as being safe. Every year, several people in California are injured or die in abandoned mines. People fall into shafts hundreds of feet deep. They stumble upon old explosives or asphyxiate on poisonous gases like carbon monoxide. They get bitten by rattlesnakes, trapped in derelict buildings, or lost in miles-long tunnels.

At the sites that are contaminated, meanwhile, contamination can mean a lot of different things.

Water flowing through old tunnels or waste rock left behind can produce acid mine drainage that’s highly toxic and corrosive. The same geological processes that produced veins of gold throughout the Sierra Nevada also brought metals like arsenic, lead, and cadmium. Most of these metals are naturally occurring in the area, but mining brings them to the surface where they can infiltrate water, absorb into plants, or be breathed in as dust.

Then there’s the mercury, added in vast quantities (especially at the hydraulic mines) to help bind with and isolate gold from the rock around it. Scientists estimate that almost 13 million pounds of mercury were lost to the environment in the 19th century and are now trapped in streams, lakes, and reservoirs.

Though the process remains poorly understood, the low oxygen environment at the bottom of reservoirs, in particular, seems to provide ideal conditions for microbes to convert mercury into methylmercury, a potent neurotoxin that can build up in fish tissue as it moves up the food web. In humans, methylmercury can cause tremors, headaches, insomnia, memory and vision loss, pain, and seizures.

Though these contaminants are known to be harmful to human health—with impacts ranging from pain and vomiting to long-term problems like asthma and cancer—linking contamination to specific health outcomes is challenging. “Exposure is complex,” says Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta, an environmental scientist at the University of Arizona. “You have not only multiple metals, but you also have multiple exposure routes.”

Ramírez-Andreotta explains that health standards for contaminants are based on multiple factors. Concentration, or how much there is, is only part of the puzzle. One must also consider how someone is exposed, whether that’s through dust, food, water, or dirt, and the type of contaminant, since human bodies absorb different elements in different ways. The risk is also based on how long and how frequently one is exposed, as well as individual traits like weight, age, and sex.

In part because it’s so complex, there’s limited research on the long-term health effects of living near a gold mine.

Sierra Streams Institute, a nonprofit based in Nevada City, about two hours north of Jackson, is trying to fill that gap. For almost a decade, Sierra Streams has been working with scientists at the University of California San Francisco and the Breast Cancer Research Project, and more recently with Ramírez-Andreotta in Arizona, to help residents understand the risks posed by toxic mining waste.

The work originally focused on breast cancer. Though breast cancer rates tend to be higher in urban areas, Nevada County, where Nevada City is, has the third highest rate of breast cancer in the state. Number two is neighboring Placer County, another rural area and hot bed of historic mining activity. And, indeed, the Sierra Streams health project found that arsenic and cadmium levels were higher in the urine of women living in Nevada County than the national average, which could increase their risk of breast cancer.

After the initial work, Sierra Streams branched out to look at how people are exposed to these harmful contaminants. They recruited residents from around the region to gather samples of water, soil, vegetables, and dust from their homes and schools. Their results suggested that residents were being exposed to arsenic and lead through soil and locally grown vegetables, at levels above state and federal screening levels in some cases. Ramírez-Andreotta recalls on several occasions having to call study participants after results came in to encourage them to quickly cover any dirt patches in their backyards.

With a small sample size and no way to control for every risk factor, the researchers can’t directly link these contaminants with long-term health issues. But it does give them a starting point to understand how people are being exposed to mining waste and what to do about it.

Taylor Schobel, the rural health coordinator for Sierra Streams, says she sees these community-led studies as a way to start a conversation about the legacy of mining and give residents the knowledge they need to protect themselves. It’s about “simple changes anyone can make,” she explains, like wet dusting, using raised beds for gardening, or just taking one’s shoes off inside. “I want to allow people to make their own decisions about day-to-day activities, to know small precautions they can take.”

But personal actions like avoiding fish that might be contaminated with mercury or keeping down arsenic-laden dust only go so far.

Engineers and geologists have devised various methods to prevent mine waste from escaping into the environment in the first place. The list of options can sound like complex physics—rhizofiltration, solidification, vapor extraction, thermal desorption—but the basic strategies are simple: take contaminated material to a landfill, treat contaminated water, or, as they plan to do at Argonaut Mine, bury the waste on-site under clean soil and plants.

At Argonaut, the EPA has focused on what they call tailings 4 area, the vacant plot of mud by the road that’s one of several contaminated ‘hotspots’ across the mine.

Deeper into the tailings area, outside of the view of passersby but just 100 feet from neighboring properties, there are eight concrete tanks left where miners once mixed in mercury and cyanide with rock to bind with the gold. There’s the crumbling assay office where owners would test the quality of the deposit, dumping out cups of liquid lead into what is now people’s backyards. Nearby, there’s an earthen dam built up over decades from a slurry of waste rock and sand.

Hillenbrand is the Remedial Project Manager for the Argonaut Superfund site. He’s quick to joke, though, that it’s “remedial as in remediation, not as in junior.” In fact, Hillenbrand has been involved with this kind of work for decades.

At first glance, he looks the part of a field geologist, in jeans with muddy wellies, a faded baseball cap, and a bright yellow safety vest. A geology class his sophomore year in college changed the course of his career, he says, and he still has a child-like enthusiasm for his job. “It’s totally geek geology stuff,” he laughs, unable to go more than a few minutes without excitedly describing the “cutting-edge technology” miners employed at Argonaut.

But that enthusiasm belies his seriousness of mission. Hillenbrand has the difficult task of figuring out how to clean up, or at least contain, the contamination at Argonaut and protect the nearby community. The EPA estimates that over 500 people live within a mile of the site.

For the last several years, they’ve just been undertaking “removal actions,” in EPA-lingo, to designate quick efforts to deal with urgent problems as the agency develops the official cleanup plan for the entire site. “We don’t want to wait five years until the whole site is understood. It’s impacting people right now,” says Hillenbrand.

While the state shored up the failing dam that threatened the town, the EPA removed truck-fulls of dirt contaminated with arsenic from a steep embankment next to the junior high school. More recently, they began removing trees, building new drainage ditches, and digging upl the contaminated dirt in tailings area 4 to create a landfill, capped with clean soil and clay to hold everything in place. “I did the old football field calculation,” Hillenbrand says of the expected size of the landfill. “It’ll be about a football field long, including the end zones, 47 feet deep.” His goal is to get the field “solar ready,” so it’ll be clean and stable enough to build a solar farm on it one day, but it’ll remain off limits to most development.

Perhaps surprisingly, not every resident has been thrilled about the plan.

In the immediate aftermath of the Superfund listing at Argonaut, the EPA excavated the yards of 11 homes adjacent to the mine that had high levels of arsenic in their dirt. Most residents, Hillenbrand says, were happy to have him.

But a 12th home down the road, which had dirt in the yard that was so acidic Hillenbrand says it was corroding the foundation of the house, has yet to be cleaned up. The homeowners refused to let the EPA on their property. In an area of the state known for high levels of, if not distrust, then certainly disinterest in government, Hillenbrand admits it’s not an unusual reaction. A lot of this work, he says, is about building trust and convincing residents that the EPA isn’t there to tank their property values or destroy these mines that some locals consider part of their heritage. “Part of it is just showing up. They see you out there. They know you have good intentions,” he says. “If you stick around long enough, people get it.”

Usually.

While Hillenbrand says most residents tend to change their mind, if the EPA isn’t invited onto the property, there’s little they can do. The only option in that scenario is to use what they call institutional controls to ensure that any potential future buyers of the property would be informed that the site is contaminated. It’s a “government way of checks and balances,” explains Hillenbrand.

Carrie Monohan, the program director for Sierra Fund, a Nevada City-based nonprofit that works on mine cleanup, says most Gold Country residents fall on a spectrum.

On the one side are those who don’t realize these sites exist. “It’s kind of out of sight, out of mind,” she says. Then there are “those that are very much aware that there was a Gold Rush, and it’s part of their identity.” Monohan suggests that, on that end of the spectrum, people are aware that these mines exist, but they don’t understand the ongoing nature of the threat. “There’s just a sense of it’s how it’s always been, so there’s not really a problem,” she says. She describes this attitude as “cultural blindness.”

Schobel, who runs the community health projects at Sierra Streams Institute, says that recruiting participants to the project has been the biggest challenge, in part because of that blindness. For example, she tried to recruit residents from the tiny town of Alleghany, only an hour northeast of Nevada City but much deeper into the mountains. Alleghany was one of the few places where gold mining remained an economic driver after World War II, and the local 16 to 1 Mine continues to operate intermittently today. When Schobel got to Casey’s Place, the only bar in town—the only business really—she recalls that the owner flat out told her, “No one is interested in this.”

Schobel suggests that part of the issue is that the risk isn’t visible. People can’t see arsenic, and they can’t know for sure that mine contamination gave them cancer. As a result, Schobel says, she often gets the response from multi-generational residents that everyone in their family is fine, so what’s the problem?

Mary Rosellen, who manages abandoned mine lands in California for the US Forest Service, knows all too well the distrust many residents hold towards government officials like herself. She grew up in Downieville, a small mining town near the northern end of State Route 49. Though it has become a world-class mountain bike destination, the forests around town are littered with old mines.

Rosellen recalls hanging out at those mines as a child and describes the attachment many Downieville residents feel towards these places. “They live on those mine sites. They grew up there. They were born there,” she says. “There’s an empathy for these sites.” Because of that attachment, there’s a bitterness, she explains, when the government changes things, even if it’s to keep people safe.

Fortunately, Rosellen thinks things are getting better and attitudes are improving. “When I started in the Forest Service, especially in the 90s, I felt like we were kind of the bad guys,” she admits. That’s no longer the case, she says, in part because the “old timers” who felt the deepest connection to these mines are passing on.

But, in an area that many people moved to exactly to escape outside interference, some suspicion remains. Downieville is not even 10 miles from Alleghany, the small town where Sierra Streams struggled to recruit participants to a health study. “This is part of their history that they love. It’s still a romanticized history,” says Schobel. “They also just want to be left alone.”

Then there’s the cost.

A 2020 report by the Government Accountability Office found that federal agencies spent $2.9 billion on abandoned mine cleanup from 2008 to 2017 across the western US. Of that, $2.5 billion was for environmental contamination, 90% of which was spent by the EPA alone.

EPA has so-called CERCLA-authority under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act that allows them to recoup some costs from anyone that’s “caused or contributed” to contamination. That can include modern mining companies trying to remine a site, landowners, or even well-intentioned state agencies and nonprofits trying to help with cleanup. But, even with the ability (and arduous responsibility) to sue those liable parties, the EPA has recouped less than half the costs of cleanup to-date, according to the same GAO report. Costs for a single project can range from as little as $100,000 to hundreds of millions.

The EPA’s Superfund list, though, is only for the “worst of the worst” sites, as Hillenbrand describes them. Thousands of other abandoned mines are too small to warrant being listed but still pose an undue burden on the state. One rough estimate suggested that cleaning up all the state’s so-called abandoned mines could cost $2.5 billion. The state Legislative Analyst’s Office cautions that that estimate is “the low end of the range.”

Nevada County’s most lucrative mine in its heyday, and one of its most popular attractions today, is Empire Mine, now a state historic park. Empire has been shuttered since 1956, but contaminants still linger in hotspots around the property. In 2007, for example, employees discovered concerning levels of arsenic and lead in a highly acidic tailings dump named the Red Dirt Pile. Because the lowest tunnels of Empire are flooded, they also found that arsenic-laden water was flowing out of the mine into a nearby creek every time it rained.

For the next several years, and for millions of dollars, California State Parks fixed up the property, creating a landfill for the most contaminated dirt and designing a water treatment system. Though the agency bore the brunt of upfront costs, in 2014 it settled with the international mining giant Newmont Mining Corporation, which operated the site after 1929. After litigation, Newmont paid almost $15 million to retroactively cover some of the cleanup and agreed to absorb most future costs.

But finding someone to help pay—a ‘potentially responsible party’ in EPA-speak—hasn’t been so easy at other mines in the area.

Like Jackson, where Argonaut Mine is, Nevada City also has its own Superfund site. Unlike in Jackson, though, no one addressed the problem until it was too late. On New Year’s Eve, 1996, a 30-foot log dam built to hold back mining debris at the Lava Cap Mine failed during a rainstorm. 10,000 cubic yards of waste flowed downstrefam, enough to cover almost five football fields in 1 foot of contaminated dirt and mud. At that point, EPA stepped in, and, in 1999, the site joined the Superfund list.

Since then, the EPA has undertaken several removal actions at Lava Cap, including digging up contaminated dirt and providing water filters to families whose wells were contaminated after the dam failure. In 2014, they completed construction of a water system to connect residents to the municipal water supply, but they still have years and millions of dollars to go.

One of the challenges at Lava Cap is that contamination stretches far beyond the original mine’s boundaries. “The definition of a Superfund site is where contamination has come to lie,” says Brian Milton, who serves the same role at Lava Cap that Hillenbrand serves at Argonaut. That includes the waste that was carried downstream during the dam failure.

The search for potentially responsible parties at Lava Cap has also been contentious and convoluted, which Milton says is “typical.”

In 2008, the Department of Justice sued several entities that had owned or operated Lava Cap Mine at various points in its history. Two subsidiaries of Newmont, which briefly owned the mine in a failed attempt to reopen it in the 1980s, quickly settled for $3 million.

But the 2008 lawsuit also mentions Sterling CentreCorp, a Canadian real estate company that purchased the land in the 1950s (Milton says it’s more challenging to recoup costs from foreign companies) and Stephen Elder, a private developer who bought the property in 1989. The EPA deemed Elder responsible in part because he had failed to comply with a state cleanup order from the 1970s that warned that the dam was already unstable. In 2018, a federal judge held Sterling and Elder liable for $32 million to help cover cleanup costs.

Elder knew there was a mine on the property when he purchased it, but he claims he wasn’t aware of how serious the problem was, nor was he told about the cleanup order or the state’s warning. He’s continued to fight the lawsuit, alleging that he’s being mistreated and doesn’t have the financial ability to pay or appeal.

The state toxics agency says the law is clear: private landowners can be held responsible, and it’s up to them to properly investigate a site before purchasing it.

But Monohan, the program director for Sierra Fund, says it’s not so black and white, especially given the cultural blindness she describes.

“The lack of curiosity has served as protection,” Monohan says, suggesting that some developers don’t undertake the necessary investigations so they can remain blissfully ignorant when developing a contaminated property. She adds that existing real estate disclosure laws, which require property owners to detail risks to a potential buyer (flooding being a common example) are insufficient when it comes to accounting for abandoned mines. As a result, there are several examples of public agencies purchasing, or being given, property with contamination that wasn’t adequately disclosed or studied beforehand.

Cleanups are often driven by development, so if a landowner can’t afford to do the work, they’ll just sit on the property until they can, even if the site is leaching out contaminants. “You’re stuck with it unless you can be creative in how you figure out to get rid of it,” Monohan admits.

For developers, getting rid of it often means giving contaminated portions of their property to local governments assuming they can fix the problem. But Monohan says that many towns and counties in the area are too small and under-resourced to handle an abandoned mine clean up, even if they only intend to build a public park or trail.

There is one advantage to putting abandoned mines into the hands of local governments. Municipalities can access funding that individuals can’t, like EPA Brownfields Grants meant to help communities rehabilitate and reuse contaminated land. With funding in hand, a small community like Nevada City can hire a nonprofit like Sierra Streams Institute or Sierra Fund to manage the cleanup work.

That’s exactly what’s happened at Providence Mine.

In old photographs, Providence looks like massive industrial operations. Today, though, there’s little left except for a crumbling foundation of an old building being overtaken by Himalayan blackberry. There’s a flat clearing, no larger than a basketball court, at the edge of thick woods, ending at a steep 50-foot cliff into Deer Creek below. The property is part of the town’s large network of open space that winds along the creek.

Kyle Leach, Sierra Streams’ geologist, has the same casual manner, muddy boots, and fascination with these sites as Hillenbrand at the EPA. Like Hillenbrand, he also has a difficult job. For over a decade, Leach has been leading several projects across Nevada City funded by Brownfields Grants, backfilling old mine shafts and replacing contaminated dirt with clean soil and plants.

He’s juggling grants in the hundreds of thousands of dollars range, not the millions of dollars available to a federal agency. Brownfields Grants also require a financial match, so Leach says they’ve had to get creative pulling together funding from various sources to cover project costs. For one, he’s learned to phase projects so he can tie up loose ends and keep the site stable until more money comes through.

“With these cleanups, you’ve got money, until it’s gone,” Leach says. “That’s why we had to do it in increments.”

The difference in scale between what’s happening at Providence versus Argonaut is clear walking around the property. Recent storm damage has brought down trees and branches, and invasive species like scotch broom are thriving across the property. The old mine shaft in the middle of the clearing that they backfilled with dirt several years before is opening again, and they’ve had to put up a fence to keep people away. It’s too expensive to use concrete or multiple feet of clean soil to cover waste like they’re doing at Argonaut. Instead, they’re using a little bit of clean soil and a lot of new plants.

Still, Leach thinks their cleanup is doing the trick, at least for the foreseeable future. The slope at the edge of the property is more gradual than it used to be, he says, and they don’t get chunks of contaminated dirt slumping into the creek anymore. Most of the site is also revegetated, which is helping keep contamination in place.

The bigger problem, though, is that they can’t work beyond the property boundary. On one end of the site, there’s a homeless camp on a bare, flat patch of dirt. Leach explains that it’s flat because it’s where the old mine furnace was, and so it’s undoubtedly toxic. But there’s a stark line between the bare ground and rocky, grassy material next to it, which Leach says marks the end of city land. The other side of the property remains in private hands. Modern political boundaries weren’t exactly a priority for the mining industry.

“We’ll clean up right to the property line,” explains Leach, “but there’s all this contamination on the other side.”

As challenging as cleanup has been, it’s only going to become more critical in the future. In California, climate change is expected to bring more frequent and intense fires and floods to the steep slopes of the Sierra. At mines, that could bring toxic waste trapped in old tunnels and dirt piles to the surface.

And, in Gold Country, mining isn’t a thing of the past. Even with today’s technology and environmental protections, gold mining is a risky venture; yet there have been several attempts to reopen old mines across the region.

In the 1990s, a mining company reopened the North Columbia Diggins, north of Nevada City. As they dug new tunnels, the miners ran into a huge fracture in the rock, which flooded the mine and drained out the surrounding aquifer like a bathtub. At least a million gallons of water flowed out every day for months, and 12 private wells in the area went dry, including the water supply for a nearby elementary school. The company replaced the wells—going out of business in the process—but water quality issues continued for years.

More recently, the town of Grass Valley has contended with a push by Rise Gold, a Canadian company, to reopen Idaho-Maryland Mine, located just a mile from the town’s main strip. It’s the third time since the 1990s that someone has tried, but gold prices are higher now than they were during the previous attempts. This month, the Nevada County Planning Commission rejected the Rise Gold project, but the county Board of Supervisors has the final say. They’re expected to make a final decision later this summer.

Ralph Silberstein, a Grass Valley local who has been a prominent voice in the campaign against the reopening, says he and other residents are concerned about several issues, including traffic, air pollution, real estate values, and, after the experience at North Columbia, drinking water. But one of the campaign’s main concerns is that Idaho-Maryland was never cleaned up after the first wave of mining. Silberstein says there are still large piles of waste around the property that could be released into the environment if the mine reopens.

“We really don’t want there to be another legacy we create of toxic contamination that goes on for another 1,000 years,” laments Silberstein.

Gold mining isn’t the industry it once was in California, but mining tourism and memory is still big business in Gold Country. And it’s personal in a place where most of the towns were built around mining and many of the locals are descendants of miners. People have developed an attachment to these places and often continue to rely on and enjoy the very sites that are contaminating their homes and poisoning their bodies, whether they realize the threat or not.

But the decades of extraction, the toxic legacy of gold mining, and the threats of the future are as much a part of the story of the Gold Rush as the tale of the original 49ers. 175 years is a long time for problems to accumulate. California can’t afford to take that long to fix it.

Leah Campbell is a proud Californian and freelance journalist who covers the environment, disasters, and science policy.

[ad_2]